In Britain today it seems your suffering only counts if you have a mortgage

In the 1970s, psychologist Stanley Milgram instructed his students to board New York subway trains around the city, approach random members of the public and ask them for their seat without offering any justification. When the students returned, they reported that perhaps surprisingly, most people were willing to give up their seat. The students also said, somewhat less surprisingly, that they found the experiment almost impossibly difficult to conduct.

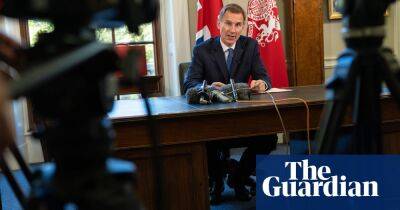

This was what’s known as a “breaching experiment”, an attempt to understand the rules of social life by briefly and deliberately breaking them. Over the past month, Britain has witnessed an extraordinary breaching experiment conducted at scale: what happens if a government acts without regard for financial markets? The results have been highly illuminating, not only for what they tell us about the likely trajectory of Liz Truss’s leadership, but for what they reveal about a host of other elites, experts and commentators who collectively get to define what counts as “sound” economic policy.

The main takeaway from the past few weeks is that no prime minister – or chancellor – can afford to ignore the views and sentiments of those who lend the state its money. This is scarcely surprising, given the lengths more orthodox politicians have gone to over the years to acknowledge the supremacy of the bond markets – but it has been graphically and quite grippingly performed before our eyes. Nobody could have predicted quite how things would play out between the September “mini-budget” and the humiliating policy U-turn and sacking of Kwasi Kwarteng three weeks later, but the fact that the markets eventually came out on top merely affirms core assumptions of the post-1970s era.

But

Read more on theguardian.com