‘You wake up wondering where your next meal is coming from’: UK food bank crisis is only getting worse

At 7.40am, when Charlotte White, the Earlsfield food bank manager, arrives for work, people are already waiting outside the redbrick building of St Andrew’s church in south-west London.

When she opens the doors a couple of hours later, many of the faces in the queue snaking out of the gate and down the road are new since the Observerlast visited in December. But not Lofe Chabal, who is near the front.

Then, the 29-year-old, who has multiple sclerosis and uses a mobility scooter, was struggling without hot water after his boiler broke. Today, he says he has been “up and down”, forming a rollercoaster trail with his hand. Having spent much of winter sleeping, he says, “I’m not a quitter”.

In December, staff at the food bank thought the situation couldn’t get any worse. Demand for the service in Earlsfield was at a record high, queues were forming outside and guests were freezing in dark homes, going without food for days. At the time, one guest said he and his two daughters were living on £4 a month after being subjected to benefit sanctions.

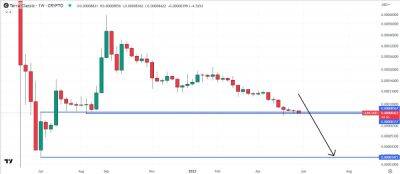

But five months on from the Observer’s special report on Food bank Britain, dependence on the facility has soared. In March, for the first time, the number of households being helped per month rose above 200 – at its peak reaching 120 a week. The monthly figure for March 2022 was 126.

Despite spring’s warmer months, there is no sign of pressures easing. “If you look at how the cost of things is going up, it’s getting worse and problems are mounting,” says White.

Demand is now so high that staff have had to reassess the services they offer. Earlier this month, guests were told that a cooked breakfast would no longer be provided – costs and numbers have made it impractical – and recently an

Read more on theguardian.com