SVB collapse presents central banks with a big headache

The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) has inevitably conjured up memories of September 2008 when the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers prompted a market meltdown, a global recession and a dramatic easing of policy from the world’s central banks.

Fears that SVB is not the only poorly regulated bank to be feeling the effects of steadily rising US interest rates have led to a rethink of what will now happen to official borrowing costs. Ultimately, that depends on whether this really is a “Lehman’s moment”, or a re-run of the stock market crash of 1987 or the failure of the hedge fund Long Term Capital Management in 1998, when the market turmoil was temporary.

On both those earlier occasions, the Federal Reserve was spooked into cuts in interest rates that proved unnecessary and which it later came to regret. As such, the fact that SVB has gone bust at a time when US inflation remains stubbornly high presents the Fed with a real headache. The Bank of England and the European Central Bank face the same dilemma.

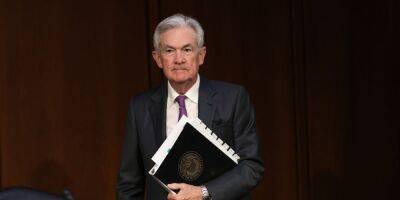

In normal circumstances, the Fed would have no hesitation in continuing to raise interest rates becausecore inflation – excluding food and energy – stands at 5.5% and is coming down at a glacial pace. Only last week the Fed chair Jerome Powell dropped a hint a fresh 0.5 percentage point increase was on the way.

But that was before the crisis at SVB. Financial markets have reacted badly to the failure of the 16th biggest bank in America, fearing it could be the first of many. Peter Warburton, chief economist with the research group Economic Perspectives thinks they are right to be worried, because the Fed has miscalculated the impact of the double whammy of higher interest rates and the selling of bonds under the process

Read more on theguardian.com